|

As I mention in the last post, the first issue of Gilbert Hernandez’s Fatima: The Blood Spinners, left me looking forward to issue #2, wondering where Hernandez will take this comic series, concerned about how he will handle an assortment of matters, and, above all else, hoping that Hernandez will take the series in smart, innovative, and thought-provoking directions.

When, a few months ago, I finally got around to buying issue #2 at a comic shop I chanced upon in Chula Vista, the owner of the store remarked, totally unselfconsciously and without any prompting from me, that with this issue Hernandez “finally” includes some sex appeal in the series. Elaborating on his observation, he indicated that he was rather disappointed with the first issue as, based on previous experience with the style of Los Bros. Hernandez, he expected/hoped for sexier images of women in this series. All the while, I was actually thinking that I was rather relieved that the character of Fatima wasn’t too sexed up in the first issue. Based on the little acquaintance I did have with the style and tendencies of Los Bros. Hernandez, sexiness is precisely what I was worried about going into the series. With the particular endorsement offered by the comic store owner (who now appeared to me in a rather creepy light), I found my worried renewed as I purchased and opened up issue #2.

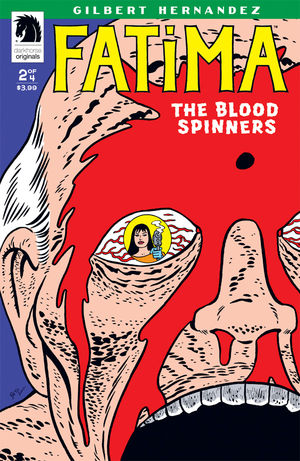

At the very least, the cover plays up Fatima’s badassness rather than any sex appeal. A zombie face covered by blood profusely flowing from a bullet hole in its forehead fills the page. Fatima only appears as a reflection in the zombie’s eye, providing a horroresque spin to John Donne’s poem, “The Good-Morrow,” in which the speaker observes as he and his lover awake next to each other the morning after a satisfying night of passion, “My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,/And true plain hearts do in the faces rest.” On the cover of issue #2, a geometry of reflections suggests an intimacy, too—in this case between Fatima and a zombie—but in contrast to the sort of emotional intimacy captured in Donne’s poem vis-à-vis physical proximity, this intimacy is mediated by the smoking semi-automatic weapon that the eponymous protagonist holds.

Although the inside cover reiterates the apparent promise made by the cover of violent gore to come (two eyeballs are exploding out of the sockets of a zombie, blood issuing forth from the now emptied out sockets) the title page works in a more suggestive (and subdued) manner. It features a half-Fatima/half-zombie head that, as it shows the head from the eyes and above, directs attention to the binaristic opposition between human subjectivity and selfhood and a zombie’s non-human lack of both.

While this latter image seems to prime a reader for an elaboration on the border between the human and the nonhuman, it actually anticipates insight into the differences between Fatima in the past and present. Most notably, the humanity of Fatima is developed vis-à-vis the revelation of a crush she formerly had on Jody, one of her coworkers at Operations. In the opening pages, we are privy to confessions such as, “Nobody got my pulse pounding like science operator Jody” (3), and, “I wish I could have been de-briefing Jody” (3). There’s even an image of the Amazonian Fatima looking like a giddy schoolgirl as she stands in the presence of her notably oblivious crush. As such imaging stands in contrast to the tough, composed numbness she exhibits in the first volume, it presents her as someone who used to be more human than we have heretofore seen.

In fact, it is interesting that Operations itself appears to have been a place where love and romance once abounded. After a few apocalyptic images of Operations now, Fatima narrates a flashback and notes, “But not long ago, ohh, [Operations] was alive, I’m telling you. The place pulsed with vitality and a sense of purpose” (2). Accordingly, in the same panel we see two pairs of obviously happy couples going about their business and the business of Operations. This continues a few pages later when we are introduced to the lesbian couple of Alexis and Teal. In this introduction, which occurs after Fatima relates, “Nobody wants to say it, but it’s looking like the end of the world” (6), Fatima says, “Maybe as long as love prevails, we’ll be safe from oblivion. The love between Alexis and Teal was a ray of hope” (6). Parallel to the evisceration of hope engendered by the zombie outbreak, however, soon enough the love between Alexis and Teal is wiped out when an Operations effort to infiltrate a dealer’s stash of Spin cure goes awry. Undercover as a couple, Teal and another agent, Chad, go to a nightclub owned by Mr. Patch, the dealer. There, Teal and Chad are exposed as Operations agents, at which points guns are drawn, zombies are unleashed, club patrons panic, and in the chaos, Chad purposely yet inexplicably shoots Teal. This breaks Alexis’s heart and registers the waning of hope wrought by the zombie outbreak.

The shooting also opens up another narrative strand: the intimation of corruption within Operations. Shortly after the death of Teal, Chad is found shot. Fatima consequently wonders whether Chad was killed because he knew something, whether the investigation with Teal and Chad inside the club was phony in the first place, and what other sorts of lies Operations might be harboring. Of course, this provides fodder for the remaining two issues in the series.

With Operations dying off, the world progressively given over to zombies, and hope for the return of anything good in the world diminishing at a precipitous rate, issue #2 ends with Fatima and Jody agreeing to put themselves into a deep freeze alongside certain other Operations agents. The plan, according to Jody: “We’ll sleep for 100 years; that’s when our people predict the true cure will be found” (19). With such wishful thinking, Jody toasts, “To a better world,” to which Fatima rejoins, “Whatever” (19), which, of course, anticipates the revealingly dismissive posturing we see in issue #1. On the very last page, the hopelessness that we see in issue #1 is set up with Fatima coming out of her deep sleep and, unbeknownst to her, Jody lurking behind her as a zombie.

In some ways, a circuit between issues #1 and #2 is brought to a close as the background for issue #1 is filled in. With the past now somewhat covered (of course, certain questions remain to be resolved), there is the feeling that with issue #3 we can start to move forward and see where this zombie outbreak (and the story of it) goes.

Now, as for the sexiness that the comic shop owner mentioned/highlighted…well, there is some skimpy workout wear worn (for some reason) by Operations agents (both male and female), glimpses of the crotch of Teal’s panties beneath the ultra-tight mini dress she dons for her undercover role, and the outline of Fatima’s apparently erect nipples beneath her tank top on the last page. Overall, there’s nothing really erotic or provocative…just enough to titillate those who are easily titillated. Of course, why these sorts of details are even included at all is what I am wondering as they are not at all necessary. They seem to be nothing more than juvenile flourishes that reflect and/or cater to stunted heterosexual male fantasy. (The crotch shot of Teal when she is dead and lying on the floor of the nightclub seems especially gratuitous.) This got me wondering about extant criticism on the imaging of women in the work of Los Bros. Hernandez. In a word, am I missing something, or is this simply pandering to/reflecting heterosexual male lust? In her essay, “Feminine Latin/o American Identities on the American Alternative Landscape: From the Women of Love and Rockets to La Perdida,” Ana Merino notes, “The Hernandez Brothers established a reputation for creating female comics characters open to historical change, whose representation can be sexual without being sexist” (175), but this only has me questioning how (and whether) such a differentiation can be drawn. Most immediately, it is something I will be thinking about as I proceed to issue #3 of Fatima.

--phillip serrato, san diego state universty

--phillip serrato, san diego state universty

Work Cited

Merino, Ana. “Feminine Latin/o American Identities on the American Alternative Landscape: From the Women of Love and Rockets to La Perdida,” The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts. Ed. Paul Williams and James Lyons. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2010. 164-178.