Published on LatinoLA.com: October 28, 2005

Sugar skulls, resplendent altares, images of dancing skeletons, and a procession at Self Help Graphics are familiar features of el Día de los Muertos in Southern California. Regardless of one’s cultural background, however, the meaning of el Día may not be so familiar. Some, for example, may see the idea of celebrating death as a kind of morbid observance. Such an impression can be attributed to the fact that death is generally feared and repressed in American society. Others (like me when I was a kid) might have been taught vaguely and inaccurately to think of el Día as a “Mexican Halloween.” In neither case is one able to fully grasp or appreciate the significance of el Día.

There are several books for children that explain el Día de los muertos. With the day fast approaching, along with celebrations scheduled throughout Southern California (just check the LatinoLA calendar), parents, teachers, and family and friends can use the following titles to inform children, clarify their understandings of the day, and generally complement efforts to keep the cultural practice alive amongst today’s younger generations.

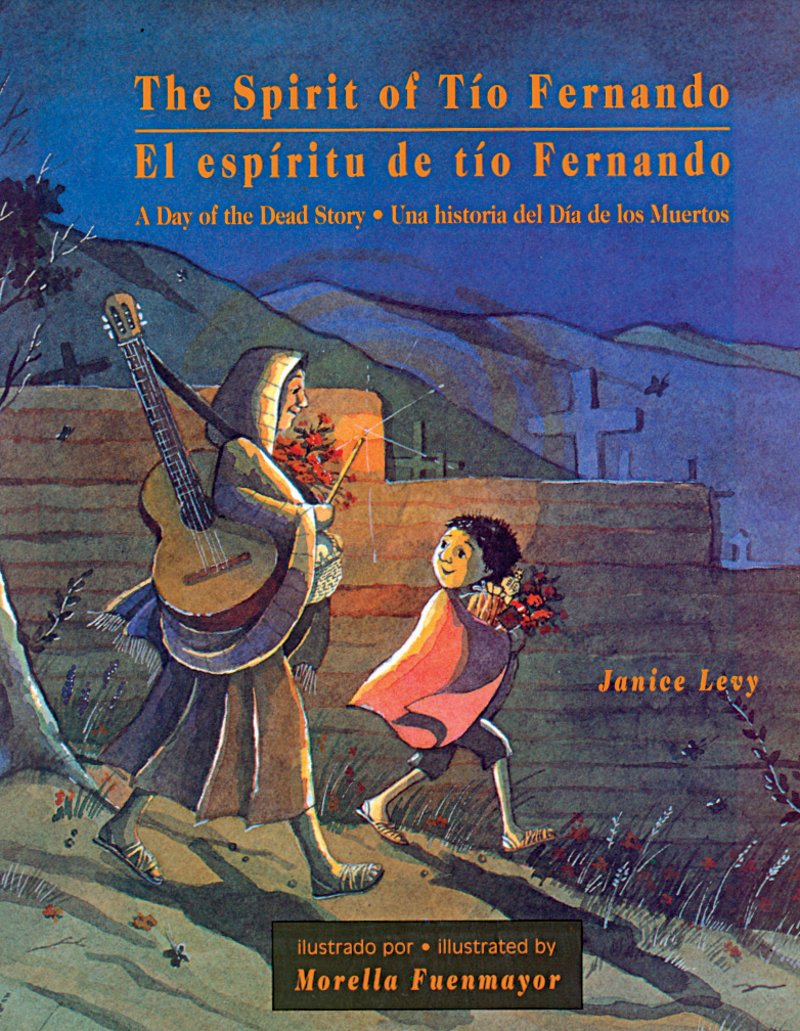

Janice Levy’s The Spirit of Tío Fernando (Albert Whitman & Co., 1995) is a splendidly accessible and engaging story about a boy who uses the Day of the Dead to remember his recently deceased uncle. The careful pace and reverent tone with which Levy depicts the careful preparation that can go into the celebration of the Day of the Dead help readers to register the Day’s importance. In the end, the Day effectively comes across not as a depressing period of mourning—as a child, including the boy in the story, may be inclined to think—but as a valuable opportunity to “remember people who have died, whom we will always love.”

The instructive value of Tony Johnston’s Day of the Dead (Harcourt, 1997) is unfortunately limited by problems with organization and focus. Set in an unnamed town in Mexico, Johnston’s story captures the anticipation with which the Day of the Dead is received via a depiction of weeks-long preparations preceding it. After 18 pages of food being prepared and children trying to sneak a taste of it, the rising action (eventually) consists of families inexplicably forming a procession that “goes walking though the street. Walking over the hill, walking to the graveyard where their loved ones lie.” Without any narrative explanation, the next several pages show families setting candles and flowers on aboveground tombs and proceeding to sing and dance amongst the crypts.

Eventually, Johnston remarks in one line on one page that the singing and dancing families “remember los abuelos,” but this gesture toward explaining what the families are doing is immediately overrun by hungry children being given the green light to feast. Not until the very last page of the book in the Author’s Note do we get an explanation of the graveyard procession and antics. For the sake of explaining the Day of the Dead and putting the ritual that the author depicts in a meaningful context, this Note should have been placed at the beginning of the book. As the book is presently structured, its capacity to introduce the Day of the Dead—which seems to be its purpose—is compromised.

In contrast, Linda Lowery does an excellent job of providing a careful background for and introduction to el Día in her Day of the Dead (Lerner, 2004) book. First, Lowery describes in a child-accessible manner the cycle of life and death to introduce the Day of the Dead as “not a sad time. It is a warm and loving time to remember people who have died. It is a time to be thankful for life.” Then to facilitate a historical appreciation and understanding of the Day, she describes, again in a child-accessible manner, its Aztec origins and the Spanish influence on it. For the remainder of the book Lowery describes the different ways that people prepare for the Day of the Dead and how they celebrate it. To her credit, she makes a careful effort to stipulate that there are different ways that people celebrate the Day in different places in the United States and Mexico. With this gesture toward regional variations, she avoids the homogenizing tendency of Levy and Johnston to imply that the Day of the Dead is celebrated the same way throughout Mexico.

One of the most whimsical books about the Day of the Dead is Luis San Vicente’s The Festival of Bones (Cinco Puntos Press, 2002). This bilingual book is a translation of a book that was originally published in Mexico. With gorgeous illustrations, it depicts a host of skeletons who, on the Day of the Dead, come out and play en masse and make their way to the graveyard for their annual festival. With singing and dancing skeletons, and characters such as “La calaca Pascuala,” whom we are told “canta/Sin pena ni temor/Aunque le falte una pata/Y en el sombrero lleve una flor,” The Festival of Bones is at once lively and funny and offers a playfully imaginative treatment of the Day of the Dead. While the narrative does not really explain the Day, there are child-friendly explanatory notes at the back of the book as well as recipes for pan de muertos and sugar skulls. This is of course the same structure that Johnston utilizes for her book. San Vicente’s purpose is different, however. Whereas Johnston’s book seems intended to inform readers about an unfamiliar tradition, San Vicente’s book, written originally for a Mexican audience, is more intended as a fanciful play on a holiday with which his implied audience is already familiar (akin to the ways that rather than provide a primer on the holidays of Halloween and Christmas, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas plays with and on them). For this reason, The Festival of Bones is not the best introduction to the Day of the Dead (Lowery’s book is), but it provides an opportunity to have some great imaginative fun with it.

Going

through all of these books, the feeling grew in me that there needs to be a

book that talks about the observance and preservation of el Día de los muertos

in communities in the United States today. Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith's Day of the

Dead (Holiday House, 1994) provided this ten years ago, but this book is

out of print already. So, how about a book that tells the meaning of el Día and

the celebration of it in Southern California in the year 2005?

Going

through all of these books, the feeling grew in me that there needs to be a

book that talks about the observance and preservation of el Día de los muertos

in communities in the United States today. Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith's Day of the

Dead (Holiday House, 1994) provided this ten years ago, but this book is

out of print already. So, how about a book that tells the meaning of el Día and

the celebration of it in Southern California in the year 2005? About Phillip Serrato:

Phillip Serrato is Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San Diego State University where he teaches classes on children’s and adolescent literature.

No comments:

Post a Comment