Published

on LatinoLA.com: October 28, 2005

Sugar

skulls, resplendent altares, images of dancing skeletons, and a procession at

Self Help Graphics are familiar features of el Día de los Muertos in Southern

California. Regardless of one’s cultural background, however, the meaning of el

Día may not be so familiar. Some, for example, may see the idea of celebrating

death as a kind of morbid observance. Such an impression can be attributed to

the fact that death is generally feared and repressed in American society.

Others (like me when I was a kid) might have been taught vaguely and

inaccurately to think of el Día as a “Mexican Halloween.” In neither case is one

able to fully grasp or appreciate the significance of el Día.

There

are several books for children that explain el Día de los muertos. With the day

fast approaching, along with celebrations scheduled throughout Southern

California (just check the LatinoLA calendar), parents, teachers, and family

and friends can use the following titles to inform children, clarify their

understandings of the day, and generally complement efforts to keep the

cultural practice alive amongst today’s younger generations.

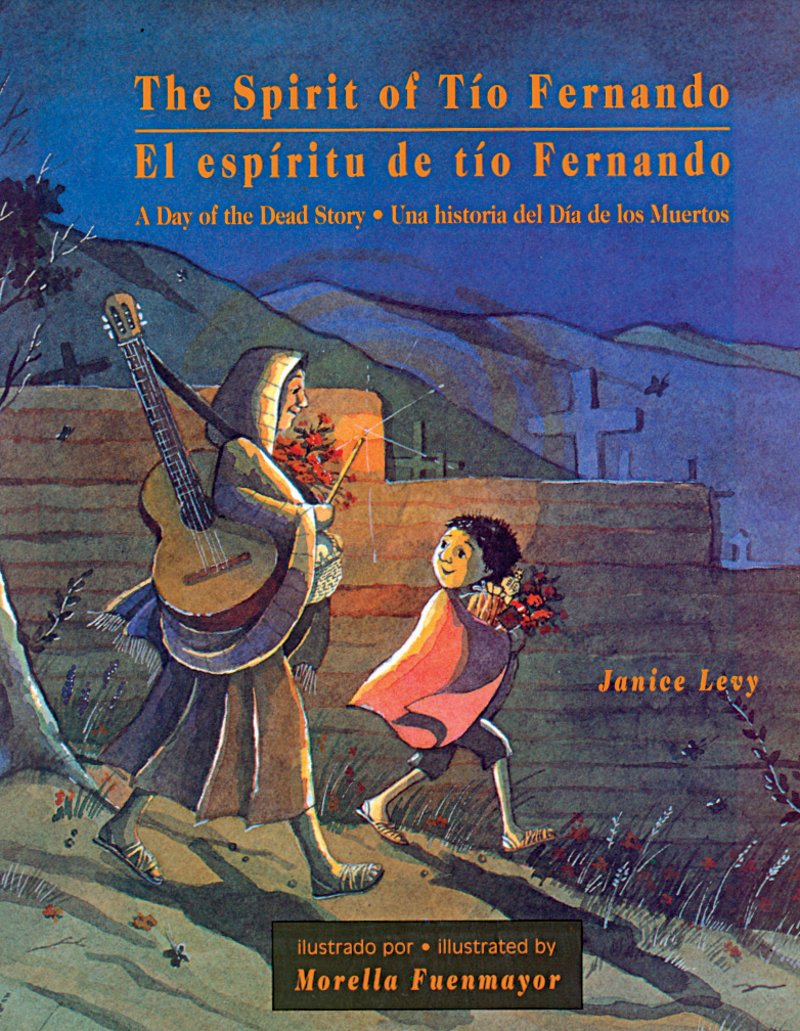

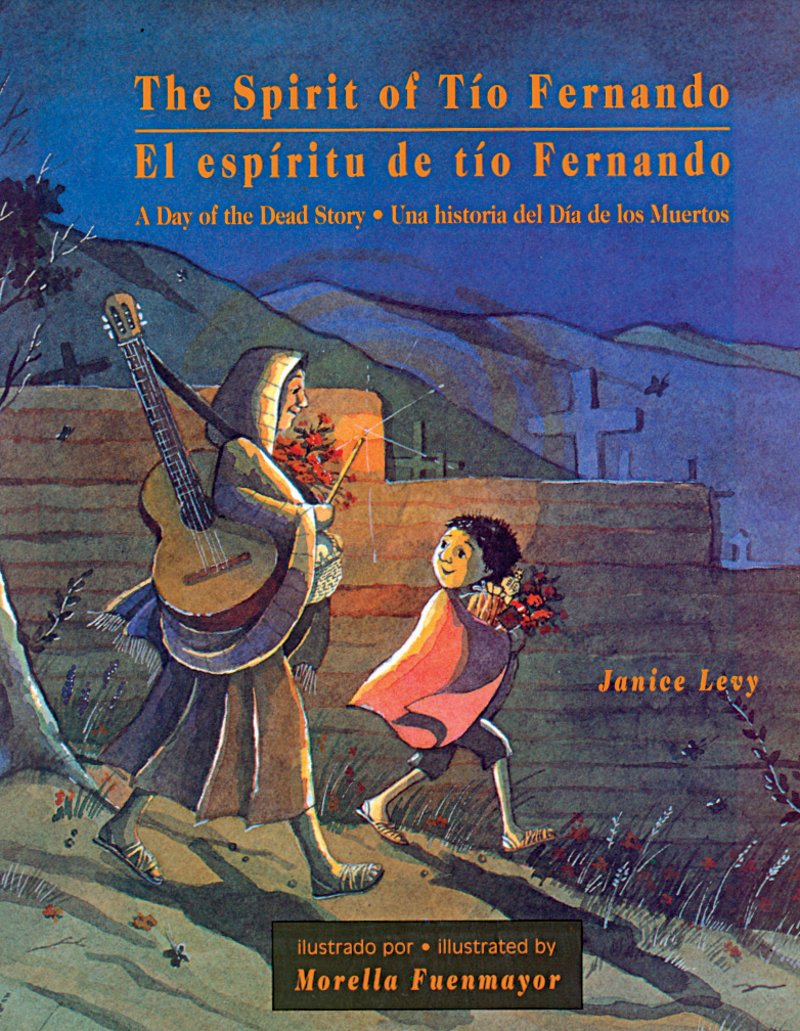

Janice

Levy’s The Spirit of Tío Fernando (Albert Whitman & Co., 1995) is a

splendidly accessible and engaging story about a boy who uses the Day of the

Dead to remember his recently deceased uncle. The careful pace and reverent

tone with which Levy depicts the careful preparation that can go into the

celebration of the Day of the Dead help readers to register the Day’s

importance. In the end, the Day effectively comes across not as a depressing

period of mourning—as a child, including the boy in the story, may be inclined

to think—but as a valuable opportunity to “remember people who have died, whom

we will always love.”

Janice

Levy’s The Spirit of Tío Fernando (Albert Whitman & Co., 1995) is a

splendidly accessible and engaging story about a boy who uses the Day of the

Dead to remember his recently deceased uncle. The careful pace and reverent

tone with which Levy depicts the careful preparation that can go into the

celebration of the Day of the Dead help readers to register the Day’s

importance. In the end, the Day effectively comes across not as a depressing

period of mourning—as a child, including the boy in the story, may be inclined

to think—but as a valuable opportunity to “remember people who have died, whom

we will always love.”

The

instructive value of Tony Johnston’s Day of the Dead (Harcourt, 1997) is

unfortunately limited by problems with organization and focus. Set in an

unnamed town in Mexico, Johnston’s story captures the anticipation with which

the Day of the Dead is received via a depiction of weeks-long preparations

preceding it. After 18 pages of food being prepared and children trying to

sneak a taste of it, the rising action (eventually) consists of families

inexplicably forming a procession that “goes walking though the street. Walking

over the hill, walking to the graveyard where their loved ones lie.” Without

any narrative explanation, the next several pages show families setting candles

and flowers on aboveground tombs and proceeding to sing and dance amongst the

crypts.

Eventually,

Johnston remarks in one line on one page that the singing and dancing families “remember

los abuelos,” but this gesture toward explaining what the families are doing is

immediately overrun by hungry children being given the green light to feast.

Not until the very last page of the book in the Author’s Note do we get an

explanation of the graveyard procession and antics. For the sake of explaining

the Day of the Dead and putting the ritual that the author depicts in a

meaningful context, this Note should have been placed at the beginning of the

book. As the book is presently structured, its capacity to introduce the Day of

the Dead—which seems to be its purpose—is compromised.

The

instructive value of Tony Johnston’s Day of the Dead (Harcourt, 1997) is

unfortunately limited by problems with organization and focus. Set in an

unnamed town in Mexico, Johnston’s story captures the anticipation with which

the Day of the Dead is received via a depiction of weeks-long preparations

preceding it. After 18 pages of food being prepared and children trying to

sneak a taste of it, the rising action (eventually) consists of families

inexplicably forming a procession that “goes walking though the street. Walking

over the hill, walking to the graveyard where their loved ones lie.” Without

any narrative explanation, the next several pages show families setting candles

and flowers on aboveground tombs and proceeding to sing and dance amongst the

crypts.

Eventually,

Johnston remarks in one line on one page that the singing and dancing families “remember

los abuelos,” but this gesture toward explaining what the families are doing is

immediately overrun by hungry children being given the green light to feast.

Not until the very last page of the book in the Author’s Note do we get an

explanation of the graveyard procession and antics. For the sake of explaining

the Day of the Dead and putting the ritual that the author depicts in a

meaningful context, this Note should have been placed at the beginning of the

book. As the book is presently structured, its capacity to introduce the Day of

the Dead—which seems to be its purpose—is compromised.

In

contrast, Linda Lowery does an excellent job of providing a careful background

for and introduction to el Día in her Day of the Dead (Lerner, 2004)

book. First, Lowery describes in a child-accessible manner the cycle of life

and death to introduce the Day of the Dead as “not a sad time. It is a warm and

loving time to remember people who have died. It is a time to be thankful for

life.” Then to facilitate a historical appreciation and understanding of the

Day, she describes, again in a child-accessible manner, its Aztec origins and

the Spanish influence on it. For the remainder of the book Lowery describes the

different ways that people prepare for the Day of the Dead and how they

celebrate it. To her credit, she makes a careful effort to stipulate that there

are different ways that people celebrate the Day in different places in the

United States and Mexico. With this gesture toward regional variations, she

avoids the homogenizing tendency of Levy and Johnston to imply that the Day of

the Dead is celebrated the same way throughout Mexico.

In

contrast, Linda Lowery does an excellent job of providing a careful background

for and introduction to el Día in her Day of the Dead (Lerner, 2004)

book. First, Lowery describes in a child-accessible manner the cycle of life

and death to introduce the Day of the Dead as “not a sad time. It is a warm and

loving time to remember people who have died. It is a time to be thankful for

life.” Then to facilitate a historical appreciation and understanding of the

Day, she describes, again in a child-accessible manner, its Aztec origins and

the Spanish influence on it. For the remainder of the book Lowery describes the

different ways that people prepare for the Day of the Dead and how they

celebrate it. To her credit, she makes a careful effort to stipulate that there

are different ways that people celebrate the Day in different places in the

United States and Mexico. With this gesture toward regional variations, she

avoids the homogenizing tendency of Levy and Johnston to imply that the Day of

the Dead is celebrated the same way throughout Mexico.

One

of the most whimsical books about the Day of the Dead is Luis San Vicente’s The

Festival of Bones (Cinco Puntos Press, 2002). This bilingual book is a

translation of a book that was originally published in Mexico. With gorgeous

illustrations, it depicts a host of skeletons who, on the Day of the Dead, come

out and play en masse and make their way to the graveyard for their annual

festival. With singing and dancing skeletons, and characters such as “La calaca

Pascuala,” whom we are told “canta/Sin pena ni temor/Aunque le falte una pata/Y

en el sombrero lleve una flor,” The Festival of Bones is at once lively

and funny and offers a playfully imaginative treatment of the Day of the Dead.

While the narrative does not really explain the Day, there are child-friendly

explanatory notes at the back of the book as well as recipes for pan de muertos

and sugar skulls. This is of course the same structure that Johnston utilizes

for her book. San Vicente’s purpose is different, however. Whereas Johnston’s

book seems intended to inform readers about an unfamiliar tradition, San

Vicente’s book, written originally for a Mexican audience, is more intended as

a fanciful play on a holiday with which his implied audience is already

familiar (akin to the ways that rather than provide a primer on the holidays of

Halloween and Christmas, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas

plays with and on them). For this reason, The Festival of Bones is not

the best introduction to the Day of the Dead (Lowery’s book is), but it

provides an opportunity to have some great imaginative fun with it.

One

of the most whimsical books about the Day of the Dead is Luis San Vicente’s The

Festival of Bones (Cinco Puntos Press, 2002). This bilingual book is a

translation of a book that was originally published in Mexico. With gorgeous

illustrations, it depicts a host of skeletons who, on the Day of the Dead, come

out and play en masse and make their way to the graveyard for their annual

festival. With singing and dancing skeletons, and characters such as “La calaca

Pascuala,” whom we are told “canta/Sin pena ni temor/Aunque le falte una pata/Y

en el sombrero lleve una flor,” The Festival of Bones is at once lively

and funny and offers a playfully imaginative treatment of the Day of the Dead.

While the narrative does not really explain the Day, there are child-friendly

explanatory notes at the back of the book as well as recipes for pan de muertos

and sugar skulls. This is of course the same structure that Johnston utilizes

for her book. San Vicente’s purpose is different, however. Whereas Johnston’s

book seems intended to inform readers about an unfamiliar tradition, San

Vicente’s book, written originally for a Mexican audience, is more intended as

a fanciful play on a holiday with which his implied audience is already

familiar (akin to the ways that rather than provide a primer on the holidays of

Halloween and Christmas, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas

plays with and on them). For this reason, The Festival of Bones is not

the best introduction to the Day of the Dead (Lowery’s book is), but it

provides an opportunity to have some great imaginative fun with it.

Going

through all of these books, the feeling grew in me that there needs to be a

book that talks about the observance and preservation of el Día de los muertos

in communities in the United States today. Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith's Day of the

Dead (Holiday House, 1994) provided this ten years ago, but this book is

out of print already. So, how about a book that tells the meaning of el Día and

the celebration of it in Southern California in the year 2005?

About

Phillip Serrato:

Phillip

Serrato is Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San

Diego State University where he teaches classes on children’s and adolescent

literature.

Going

through all of these books, the feeling grew in me that there needs to be a

book that talks about the observance and preservation of el Día de los muertos

in communities in the United States today. Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith's Day of the

Dead (Holiday House, 1994) provided this ten years ago, but this book is

out of print already. So, how about a book that tells the meaning of el Día and

the celebration of it in Southern California in the year 2005?

About

Phillip Serrato:

Phillip

Serrato is Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San

Diego State University where he teaches classes on children’s and adolescent

literature.

Published on LatinoLA,com: June 27, 2002

As

Shakira and Paulina Rubio lead a second wave of Latin artists pursuing

mainstream pop music success in the United States, La Banda Skalavera and Los

Lobos are making Chicano rock that has not been crafted to receive Top-40

airplay. Especially refreshing is the two Southern California Chicano bands’

ability to inspire Latinismo at a time when the two Latina divas are looking

more and more like sexed-up real-life Barbie dolls.

Of

course, the mainstream, pop-in-English musical directions that Shakira and

Rubio are presently taking are, on several levels, productive artistic and

commercial avenues to follow. The two women are accessing the kind of profit

and popularity that other Latinas/os such as Ricky Martin. Marc Anthony, and

Jennifer Lopez have only recently begun to attain. Moreover, their explorations

of “non-Latin” musical forms contribute to the expansion of the parameters of “Latina/o

pop music.”

Nonetheless,

with songs such as “Whenever, Wherever,” “Underneath Your Clothes,” and “Don’t

Say Goodbye,” Shakira and Rubio are really only making the kind of

non-racially-specific “art without thorns” that Chicano performance

artist/critic Guillermo Gómez-Peña says is the only kind of Latino/a art that

can be expected to have mainstream appeal in the United States. Like previous

hit songs by Martin, Anthony, and Lopez, the latest English-language singles by

Shakira and Rubio are catchy and kind of exotic, yet they are ultimately not

significantly different from the other Top-40 fare that stations such as KIIS

recycle.

In

contrast, La Banda Skalavera and Los Lobos unabashedly frame themselves as

Chicano bands and indulge their affinity for playing with traditional Latin

rhythms. Oblivious to mainstream Top-40 popularity contests, the two bands

unapologeticaly roll around in Chicanismo/Latinismo.

I

saw and heard La Banda Skalavera for the first time at the Festival Latino at

UCLA a few months ago. They offered an energetic fusion of ska and punk that

got a lot of people to get up and dance “con ganas.” Touches of traditional

rhythms, along with a playful horn section, made the performance particularly enjoyable.

Because the majority of the song lyrics were delivered in Spanish and driven by

Latin rhythms, the band also managed to appeal to the attendees’ Latino pride,

and this rendered the performance even more inspiring.

As

occurs with many artists, the band?s 15-track debut release, "No Está

Mal", doesn’t convey the same energy that the band manufactures live.

Nonetheless, the CD offers a fascinating and fun listening experience. It

contains animating ska/punk fusions that feature gestures toward cumbia and 80’s-era

hard rock. While the title-track comments on finding beauty in life, most of

the other songs revolve around the travails of love. Among the more

successfully hyperactive songs are “Hipócrita,” “Veinticuatro,” “Cómo Jodes,” “Ya

No,” and the title cut. Other songs such as “Vamos a Bailar” and “Cumbia del

Loco” are especially alluring because they are built on rich Latin grooves.

“Crushed,”

“I Love You So,” and “Tú” are endearing yet by no means syrupy songs of

romantic yearning that keep the CD (and the band) musically and thematically

interesting. “Memories,” however, comes across as a throwback to overwrought ’80s

power ballads. Not as interesting as the other songs on the CD, musically and

thematically it stalls the disc.

The

horn section gives songs such as “No Está Mal” and “Sueño pa’ Mí” a playful and

exhilarating vibe that complements the Latinismo that the songs simultaneously

provoke. Electric guitar blazes on “Hipócrita,” “Veinticuatro,” and “Ya No”

remind one of anthemic ’80s power rock and reflect the musical playfulness that

the band likes to indulge. At times, though, the hard-rock riffs disrupt the

musical cohesion of a song. “Mala Cabeza” is a Spanish-language hard-rock rap

track that reminds one of Molotov that doesn’t fully fit within the musical

trajectory of the disc. It does reflect, however, the band’s investment in

exploring various musical forms in a way that suggests the extent to which

post-modern Chicano identity and experience have been hyper-crisscrossed by

different cultural influences. The post-modern Chicano fun of “Todo Cambiará”

is rooted in the shifts between multiple musical genres that can occur in the

span of three minutes. As this song documents the band’s boundless love for

diverse types of music, it simultaneously invites listeners to share in this

love.

At

times the vocals and/or music remind one of Los Fabulosos Cadillacs, Madness,

and Sublime, but La Banda Skalavera mostly manages to maintain an appealing and

respectable originality. The dominant impression of this CD is that the guys

genuinely enjoy making music and playing with musical forms. In the future they

will hopefully maintain their vitality and daring spirit and continue to offer

up music that is interesting and exhilarating and that stimulates Latinismo.

In

contrast, La Banda Skalavera and Los Lobos unabashedly frame themselves as

Chicano bands and indulge their affinity for playing with traditional Latin

rhythms. Oblivious to mainstream Top-40 popularity contests, the two bands

unapologeticaly roll around in Chicanismo/Latinismo.

I

saw and heard La Banda Skalavera for the first time at the Festival Latino at

UCLA a few months ago. They offered an energetic fusion of ska and punk that

got a lot of people to get up and dance “con ganas.” Touches of traditional

rhythms, along with a playful horn section, made the performance particularly enjoyable.

Because the majority of the song lyrics were delivered in Spanish and driven by

Latin rhythms, the band also managed to appeal to the attendees’ Latino pride,

and this rendered the performance even more inspiring.

As

occurs with many artists, the band?s 15-track debut release, "No Está

Mal", doesn’t convey the same energy that the band manufactures live.

Nonetheless, the CD offers a fascinating and fun listening experience. It

contains animating ska/punk fusions that feature gestures toward cumbia and 80’s-era

hard rock. While the title-track comments on finding beauty in life, most of

the other songs revolve around the travails of love. Among the more

successfully hyperactive songs are “Hipócrita,” “Veinticuatro,” “Cómo Jodes,” “Ya

No,” and the title cut. Other songs such as “Vamos a Bailar” and “Cumbia del

Loco” are especially alluring because they are built on rich Latin grooves.

“Crushed,”

“I Love You So,” and “Tú” are endearing yet by no means syrupy songs of

romantic yearning that keep the CD (and the band) musically and thematically

interesting. “Memories,” however, comes across as a throwback to overwrought ’80s

power ballads. Not as interesting as the other songs on the CD, musically and

thematically it stalls the disc.

The

horn section gives songs such as “No Está Mal” and “Sueño pa’ Mí” a playful and

exhilarating vibe that complements the Latinismo that the songs simultaneously

provoke. Electric guitar blazes on “Hipócrita,” “Veinticuatro,” and “Ya No”

remind one of anthemic ’80s power rock and reflect the musical playfulness that

the band likes to indulge. At times, though, the hard-rock riffs disrupt the

musical cohesion of a song. “Mala Cabeza” is a Spanish-language hard-rock rap

track that reminds one of Molotov that doesn’t fully fit within the musical

trajectory of the disc. It does reflect, however, the band’s investment in

exploring various musical forms in a way that suggests the extent to which

post-modern Chicano identity and experience have been hyper-crisscrossed by

different cultural influences. The post-modern Chicano fun of “Todo Cambiará”

is rooted in the shifts between multiple musical genres that can occur in the

span of three minutes. As this song documents the band’s boundless love for

diverse types of music, it simultaneously invites listeners to share in this

love.

At

times the vocals and/or music remind one of Los Fabulosos Cadillacs, Madness,

and Sublime, but La Banda Skalavera mostly manages to maintain an appealing and

respectable originality. The dominant impression of this CD is that the guys

genuinely enjoy making music and playing with musical forms. In the future they

will hopefully maintain their vitality and daring spirit and continue to offer

up music that is interesting and exhilarating and that stimulates Latinismo.

Los

Lobos most obviously signal their unwavering commitment to Chicanismo through

the title of their just-released CD. Good Morning Aztlán brings into

2002 a term and concept that activists and cultural workers used during the

Chicano Movement in the 1970s to nurture a sense of raza consciousness amongst

Chicanos and Chicanas in the U.S. Southwest. By referencing Aztlán, Los Lobos

defiantly announce that even in the new millennium, as other Latino/a artists

pursue crossover appeal, they will continue to position themselves as a Chicano

band from East L.A.

At

the outset of the CD it is clear that Los Lobos are not going to offer up

formulaic Top-40 fare. “Done Gone Blue” resembles not the polished production

of Shakira’s “Whenever, Wherever” or “Underneath Your Clothes,” but raw garage

rock that grabs a listener on a visceral level. One can easily imagine this

song and the other garage rocker, “Good Morning Aztlán,” causing a live

audience to explode. Track two, “Hearts of Stone,” is comparatively more

cleanly produced, but it follows a slow, funky vibe that distinguishes the song

as a product of a Los Lobos jam session.

While

“Malaqué” sounds like an indigenous hymn bemoaning the mass flight of migrants

from their Mexican homes and mesmerizes the listener with its harp work, “Luz

de Mi Vida” and “Maria Christina” engage the listener through methodical

percussion work. The Spanglish that is used in “Luz de Mi Vida,” however, feels

more forced than an instance of the bilingual code-switching that Latinos and

Latinas often perform naturally as they try to express themselves. The electric

guitar solo in the cumbia-driven “Maria Christina” teases out wonderfully the

sensuality that the sultry Spanish vocals and percussion collaboratively

create.

Thematically,

the songs on Good Morning Aztlán are not as restricted to East L.A./Chicano

Studies concerns as the cover art and the title of the CD might lead one to

expect. “Luz de Mi Vida,” “Good Morning Aztlán,” and “The Big Ranch” do depict

life in Southern California barrios while “Tony y Maria” narrates the

experiences of a migrant Mexican couple in Los Angeles. The lyrics of other

songs, though, betray an obsession with human community and the fate of the

world.

Some

music reviewers have suggested that the themes of love, loss, anguish, and

uncertainty that suffuse the CD reflect Cesar Rosas’s devastating loss of his

wife. It also seems possible, though, especially since Rosas penned the lyrics

for only a few songs, to read several of the tracks as responses to September

11.

“The

Word,” for example, voices uncertainty about the current state of world affairs

with lyrics such as, “The word’s out on the street/round everyone you meet/Things

are not the way they used to be.” Later, in “What in the World,” an apparent

nod to John Lennon reveals itself in the form of an appeal cathected with a

latent sense of despair: “Imagine, oh imagine what this world/oh what this

world could be.?”

Even

“Tony y Maria” is less about Mexican immigration as a social or political issue

than it is about a couple’s love and commitment to each other. Lines such as, “We

promised that we’d care for one another/said his wife/now and for the rest of

our lives” render the song just gorgeous, steeped as it is in existentialist

pathos. It’s unfortunate that this stunning song is followed by the solid

rocker “Get to This,” for the energy of the latter track quickly blows away the

appreciation of interpersonal love and commitment that “Tony y Maria” nurtures.

By

the final song, though, the listener has another chance to contemplate how

beautiful interpersonal love and commitment can be. With a hypnotic background

of distorted electric guitars, the song explores the terror that one can

experience when facing life alone. Ultimately, the song and the CD conclude with

the optimistic idea, “Heart to heart we can’t be wrong/soul to soul in this

small corner of the earth/we can be strong.”

Whether

the “small corner of the earth” that is referenced is Aztlán, our homes, or the

various other spaces we share with the many people in our lives, the song

points toward the importance of companionship and mutual support at a time when

the world is getting more and more violent and full of hate.

Los

Lobos most obviously signal their unwavering commitment to Chicanismo through

the title of their just-released CD. Good Morning Aztlán brings into

2002 a term and concept that activists and cultural workers used during the

Chicano Movement in the 1970s to nurture a sense of raza consciousness amongst

Chicanos and Chicanas in the U.S. Southwest. By referencing Aztlán, Los Lobos

defiantly announce that even in the new millennium, as other Latino/a artists

pursue crossover appeal, they will continue to position themselves as a Chicano

band from East L.A.

At

the outset of the CD it is clear that Los Lobos are not going to offer up

formulaic Top-40 fare. “Done Gone Blue” resembles not the polished production

of Shakira’s “Whenever, Wherever” or “Underneath Your Clothes,” but raw garage

rock that grabs a listener on a visceral level. One can easily imagine this

song and the other garage rocker, “Good Morning Aztlán,” causing a live

audience to explode. Track two, “Hearts of Stone,” is comparatively more

cleanly produced, but it follows a slow, funky vibe that distinguishes the song

as a product of a Los Lobos jam session.

While

“Malaqué” sounds like an indigenous hymn bemoaning the mass flight of migrants

from their Mexican homes and mesmerizes the listener with its harp work, “Luz

de Mi Vida” and “Maria Christina” engage the listener through methodical

percussion work. The Spanglish that is used in “Luz de Mi Vida,” however, feels

more forced than an instance of the bilingual code-switching that Latinos and

Latinas often perform naturally as they try to express themselves. The electric

guitar solo in the cumbia-driven “Maria Christina” teases out wonderfully the

sensuality that the sultry Spanish vocals and percussion collaboratively

create.

Thematically,

the songs on Good Morning Aztlán are not as restricted to East L.A./Chicano

Studies concerns as the cover art and the title of the CD might lead one to

expect. “Luz de Mi Vida,” “Good Morning Aztlán,” and “The Big Ranch” do depict

life in Southern California barrios while “Tony y Maria” narrates the

experiences of a migrant Mexican couple in Los Angeles. The lyrics of other

songs, though, betray an obsession with human community and the fate of the

world.

Some

music reviewers have suggested that the themes of love, loss, anguish, and

uncertainty that suffuse the CD reflect Cesar Rosas’s devastating loss of his

wife. It also seems possible, though, especially since Rosas penned the lyrics

for only a few songs, to read several of the tracks as responses to September

11.

“The

Word,” for example, voices uncertainty about the current state of world affairs

with lyrics such as, “The word’s out on the street/round everyone you meet/Things

are not the way they used to be.” Later, in “What in the World,” an apparent

nod to John Lennon reveals itself in the form of an appeal cathected with a

latent sense of despair: “Imagine, oh imagine what this world/oh what this

world could be.?”

Even

“Tony y Maria” is less about Mexican immigration as a social or political issue

than it is about a couple’s love and commitment to each other. Lines such as, “We

promised that we’d care for one another/said his wife/now and for the rest of

our lives” render the song just gorgeous, steeped as it is in existentialist

pathos. It’s unfortunate that this stunning song is followed by the solid

rocker “Get to This,” for the energy of the latter track quickly blows away the

appreciation of interpersonal love and commitment that “Tony y Maria” nurtures.

By

the final song, though, the listener has another chance to contemplate how

beautiful interpersonal love and commitment can be. With a hypnotic background

of distorted electric guitars, the song explores the terror that one can

experience when facing life alone. Ultimately, the song and the CD conclude with

the optimistic idea, “Heart to heart we can’t be wrong/soul to soul in this

small corner of the earth/we can be strong.”

Whether

the “small corner of the earth” that is referenced is Aztlán, our homes, or the

various other spaces we share with the many people in our lives, the song

points toward the importance of companionship and mutual support at a time when

the world is getting more and more violent and full of hate.

Published

on LatinoLA.com: June 4, 2001

Since

the 1980s and the emergence of Latina feminism, there has been an increasing

amount of critical attention devoted to gender roles and expectations in Latino

cultures. Led by noted theorists Gloria Anzaldua and Cherrie Moraga, Latina

feminists in the 1980s began talking about their personal experiences as women

to expose and critique the oppression and abuse that Latinas often endure.

This

critical work also initiated the exploration of how masculinity is usually

defined in Latino cultures and how the patriarchal organization of the family

affects both men and women as well as their sons and daughters. Over the last

ten years, there has been more and more discussion about Latino masculinity by

both male and female critics and artists in an effort to understand how it

works in Latino cultures and how Latino men are pressured to be "real

men." One consequence of this increased examination of Latino masculinity

is a growing recognition that it can and must take new forms.

The

one-woman show Afro-Spic starring Maria Costa clearly follows in the

footsteps of the Latino/a gender studies work of the last two decades.

Advertised as a "comedic journey of Latina liberation and taming the macho

man," Costa primarily attempts to portray the obstacles and

anxieties that Latinas must overcome as they struggle to arrive at a sense of

self-reliance and, ultimately, self-respect. Toward the end the show begins

turning toward an exploration and critique of machismo. Overall, the show is

driven by good intentions and is marked by some outstanding features. However,

Afro-Spic really does not break any new critical ground, and over the last few

pieces its focus gets a bit muddled as it tries to cover too much ground.

Costa

is definitely the right person for this show. Her dexterous ability to

nail-down the idiosyncrasies of the different characters that she portrays in

the eight pieces helps her to convey an appropriate emotional depth for each

one. Unfortunately, on the night that I saw the show Costa performed to a

painfully small audience that did not provide her with much energy to feed off

of. The fact that her performance space was the second floor of a restaurant

did not help either, and ultimately it felt like this critical work deserved a

different context.

The

show opens boisterously with Costa leading a line of four Afro-Cuban drummers.

As she makes her way through the audience, she stops to gyrate in front of or

with a few people. This is an effective way to begin, for it captures the

audience's attention and, as often occurs when Latin music is played, triggers

a powerful sense of latinidad amongst those in attendance. By tapping into a

Latino consciousness at the outset, a receptive audience gets secured for the

first piece, "Libre Como el Viento."

In

this opening piece, Costa is Rebecca Gonzalez, a Cubana who invites the

audience to party with her because she has just graduated from high school. At

first she tells the audience how happy she was strutting across the stage at

the graduation ceremony, "waving and feeling sexy." This narrative

soon devolves, however, into a confession about her relationship with her

abusive husband Pedrito who "has a lot of fucked up shit to deal

with." Thus in this very first piece, we meet a Latina who clings to an

ethos of "pa'delante" yet is violently prevented from realizing her

full potential by a man in her life who clings to an ethos of machismo. The

conspiracy of culture and tradition with the containment of Latinas is next

thrown into relief when Rebecca relates that in a vision she had her mother

basically dismissed Pedrito's reprehensibility by saying that all that matters

is that he loves her.

But

it turns out that instead of being completely cornered by her lover, family,

and cultural tradition, Rebecca -- drawing courage from her perfectly-chosen

hero, Tina Turner -- opted to liberate herself and knock out Pedrito. As the

drummers burst back into action at this point in apparent celebration of Rebecca's strength, I found myself thinking that the current hit

"Survivor" by Destiny's Child would have been appropriate, too.

The

next three pieces -- "Diva," "R.E.S.P.E.C.T.," and

"Pelo Malo" -- continue to foreground the theme of Latina

self-respect. In "Pelo Malo," Costa is a Chicana child named Marisela

who, already at her young age, is acutely aware that her dark skin is not

"beautiful." "R.E.S.P.E.C.T." effectively uses irony to

make its point about the importance of Latina self-respect. In this piece,

Costa is a self-proclaimed strong Latina who ultimately is a conflicted

heroine. At the same time that this woman assertively yells out to her

boyfriend, "Nigger, wait!" she fusses over looking beautiful in an

effort to secure a man who will make her feel "loved, desired, and treated

like a lady." At the end of the piece she strikes a pose and asks,

"How do I look? Beautiful, huh? Something missing?" and she then

proceeds to remove her jacket to expose some more skin. Of course, the irony

and point is that what is missing is some self-respect.

In

my estimation, the smartest moment of the show occurs in "Diva."

"Diva" is about a woman who has a feminist consciousness yet is

simply unable to escape completely macho domination. As she relates, "I

went to the testosterone dark side and I loved it. Yes, me, a strong woman fell

for a macho." This piece effectively portrays a Latina feminist who struggles to enjoy a heterosexual desire that does not compromise her politics. It thus captures a vexing issue that continues to be debated within

feminist circles. At one point Costa mimics sex with her macho lover. Initially on top and approaching orgasm, she is soon enough brought down, turned around,

and entered from behind. On all fours pretending that her lover is forcefully

thrusting into her, Costa uncomfortably reveals to the audience that her macho

man wants her to be a wife, cook, and the mother of his children. Although this

simulation of sex seemed to make a few people in the audience uncomfortable, it

was a brilliantly pornographic metaphor for the multi-leveled (re)subordination

of this Latina.

Over

the rest of the show, the play's focus gets dispersed. Latinos in Hollywood,

Latino homosexuality, and Latino machismo are the subjects of the next three

pieces. In particular, "Hispanic American Princess" -- which suggests

that if Latinos/as want to work in Hollywood they can either bleach their hair

and act white or play the parts of criminals -- seemed to swerve too far from

the trajectory that the first three pieces establish.

With

"Perfectly Fabulous" and "Confessions of a Macho," the show

comes back to its emphasis on gender roles and expectations by attending

briefly to Latino masculinity. In "Perfectly Fabulous," we are

introduced to Lola, a Cuban-Nuyorican drag queen who "tried for years to

be the man that [my father] wanted me to be" but years ago liberated

himself from compulsory heterosexuality and embraced his queer identity. In

"Confessions of a Macho," Lola's aging father reveals how he has been

a macho (e.g., he is unsure of how many illegitimate children he has fathered)

yet at the very end manages to tell Lola, "I love you."

This

understated moment of change sets up Costa's spoken-word poem,

"AFROSPIC," in which she talks about the necessity of change in the

face of the fear of change. A few factors, however, get in the way of the poem

being as inspiring as it could have been. First of all, the call for change

would feel more urgent if the play itself had a tighter focus. Because of the

dispersal of the play's focus over the last half, the call to change in Afro-Spic feels too general.

Also,

the concluding call for change is not unfamiliar. In many ways, Afro-Spic reperforms work that others have done. Many writers have already talked about

the disparagement of the brown body inside and outside of Latino cultures, and

the Hollywood dilemma/problem is constantly under discussion. Moreover,

"Libre Como el Viento," "Diva," "R.E.S.P.E.C.T.,"

"Perfectly Fabulous," and "Confessions of a Macho" echo a

bit too much the performance work of Luis Alfaro and John Leguizamo, especially

the latter's Mambo Mouth and Freak.

Of

course, it is perfectly possible that for some who see Afro-Spic the show is

an exhilarating introduction to the critical issues that for others are not so

new.

And makes it worthwhile, no?

Afro-Spic

plays Saturdays at 7 p.m.. Hudson Mainstage Theatre, 6539 Santa Monica Blvd.,

Hollywood. 323 288-9034. Reservations encouraged. $10.

Going

through all of these books, the feeling grew in me that there needs to be a

book that talks about the observance and preservation of el Día de los muertos

in communities in the United States today. Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith's Day of the

Dead (Holiday House, 1994) provided this ten years ago, but this book is

out of print already. So, how about a book that tells the meaning of el Día and

the celebration of it in Southern California in the year 2005?

Going

through all of these books, the feeling grew in me that there needs to be a

book that talks about the observance and preservation of el Día de los muertos

in communities in the United States today. Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith's Day of the

Dead (Holiday House, 1994) provided this ten years ago, but this book is

out of print already. So, how about a book that tells the meaning of el Día and

the celebration of it in Southern California in the year 2005?